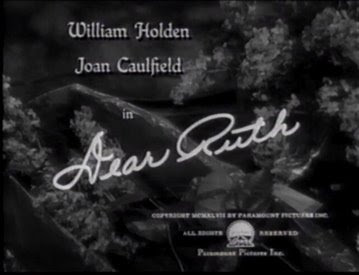

Dear Ruth

If Calcutta represents Paramount's more quotidian style reserved for action films, Dear Ruth (William D. Russell) represents the quintessential Paramount A picture: high production values, well-honed, theatrical-quality script, and generic appeal. In this case, the film is a satirical comedy, part of a strain of wisecracking comedies emerging from the 30s screwball comedy but shifting in its class milieu and referents. It might even be said to be a personal subgenre of writer Norman Krasna. To my eye, it's the best argument that what drove romantic comedy success in old Hollywood was not a particular gender role configuration (helpful that might be) but a means of nurturing and using a talent pool of writers riffing off one another. Rather than a culturalist account of the screwball comedy, I'd give an industrial account.

The conflict begins when an Air Force Lieutenant, Bill Seacroft (played by a dreamy eyed, ever-smiling William Holden) comes to woo the small-town girl Ruth (Joan Caulfield), who had written him letters overseas. Only Ruth did not write the letters; it was her political activist high-school sister Miriam. You can imagine where things take off from there.

I'm wondering if 1947 serves as a watershed year, the last time that World War II so dominated the American screen. I'll have to watch more late 40s/early 50s films to know for sure (Twelve O'Clock High, for instance comes 2 years later in 1949), but it's remarkable that the war is pretty much told in present tense here, much as it is in Voice of the Turtle.

The mammy figure of Dora (Marietta Canty) would be unremarkable, perhaps, were the narration not so blatant in marginalizing her. I am not the most naive viewer, but even I was shocked at the tracking shot that completely forgets about Dora's existence.

Of course, this is a tough heritage to face in studying/teaching classic Hollywood. The whiteness and marginalization/trivialization of African-American characters is omnipresent and egregious. I happen to think the films are still valuable to watch on a number of levels - as aesthetic experience, as historical index, and as model for what the medium can do. And there's a case to be made that in other areas the 1940s have political possibilities later shut down. (Miriam, for instance, represents a radical Eleanor Rooseveltian politics that are often glossed over by cultural memory of the period as homogenous.) That said, I can empathize with those who would prefer to spend their time with less offensive racial representations.

Comments