The Other Archive Effect

Toponomy

dir. Jonathan Perel, 2015, Argentina

In her book, The Archive Effect, Jaimie Baron argues that appropriated nonfiction footage, i.e. archival footage, relies on and invokes an archive effect, a spectatorial experience of presentness in relation to the cinematic past.

Here, as in the general use of the term “archive footage,” the archive is in fact any collection of older moving-image or audio-visual footage accessible. But watching Jonathan Perel’s Toponomy, I wondered about the other kind of archive, namely an official repository of documents in which a knowledge system provides an archival context for the documents’ meaning. It’s not a hard and fast distinction, but in comparsion to the more official kinds of archiving, the loose invocation of the "archive" to refer to a totality of older moving-image material is different than localized archiving of such material.

Toponomy is structured in four segments, each corresponding to a quarter of a planned town in Argentina, designed during the dictatorship to replace the existing indigenous community after a political uprising. The film's structure presents four with a shows the sameness of modernist urban design's symmetry and by implication the rigidity of the forced urban planning.

Toponomy is structured in four segments, each corresponding to a quarter of a planned town in Argentina, designed during the dictatorship to replace the existing indigenous community after a political uprising. The film's structure presents four with a shows the sameness of modernist urban design's symmetry and by implication the rigidity of the forced urban planning. The places are either evacuated of people or play off a dynamic of populated/evacuated, as in two shots (seen right) - the first an emtpy basketball court layered with walla sounds of children playing and talking, the second a shot that starts off depopulated until a human figure enters the frame.

The places are either evacuated of people or play off a dynamic of populated/evacuated, as in two shots (seen right) - the first an emtpy basketball court layered with walla sounds of children playing and talking, the second a shot that starts off depopulated until a human figure enters the frame.

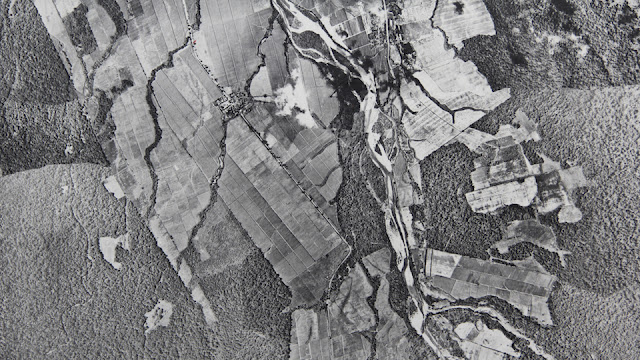

The segments of poetic-observational footage of the town are bracketed each by a prologue of documents from the government - aerial photographs, city plans, and executive orders creating the new cities.

I would divide the common practices of archival footage in documentary into three broad approaches. The most traditional is the use of a range of moving-image footage from multiple sources, both as an index of the topic and to give a fictive life to the nonfiction argument. Eyes on the Prize, for instance, has an amazing amount of televisual recording of Civil Rights events. Combined with the editing, structure, and voiceover narration, these provide a composite historical account of the movement.

The second approach, that spans from experimental doc to newer more mainstream features, would be a single-source archival film, such as Our Nixon or Black Power Mixtape or the work of Peter Forgacs. The raison d'etre of these films is the unearthing of a single collection of audiovisual material and compilation into a new cinematic experience.

Toponymy, in my eye, uses a third approach, which understands the archival document for its role in a non-cinematic archive. The segment prologues have such an impact because they are not merely older footage or historical in nature or part of a collection of cinematic/televisual footage. They shift the register of referent, to the governmental or juridicial. Mainstream docs can do this, too (see the legal procedural documentary's fetish of court documents) but the editing of Toponymy makes legible and interrogates the document-ness of the document.

Comments